The world had never seen anything like the graceful iron form that rose from Paris’ Champ de Mars in the late 1880s. The “Eiffel Tower,” built as a temporary installation for the Exposition Universelle de 1889, became an immediate sensation for its unprecedented appearance and extraordinary height. It has long outlasted its intended lifespan and become not only one of Paris’ most popular landmarks, but one of the most recognizable structures in human history.

In 1884, the French government announced the planning of an international exposition to honor the hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution of 1789 – the fourteenth such fair to be held in France since the close of the 18th Century. Shortly afterward, the French civil engineer Gustave Eiffel proposed the construction of an iron tower 300 meters (984 feet) tall as a ceremonial gateway for the Exposition.[1] Similar proposals had been put forth multiple times at least since the 1830s, and in particular before the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876; however, these projects ultimately never came to fruition.[2]

Eiffel was well established in the field of ironworking in the mid-1880s. His firm, one of the largest in France, had designed a number of significant structures, including the internal framework for the Statue of Liberty.[3] Eiffel had also aided in the engineering of cavernous galleries and pavilions for the Expositions of 1867 and 1878. Despite this illustrious portfolio, the firm was best known for its major railway bridges, most notably the Viaduct of Garabit – then the world’s tallest bridge. It was the experience of creating these enormous wrought-iron structures in particular that would later inform the design of the Eiffel Tower.[4]

Although it was eventually named for Gustave Eiffel, the Eiffel Tower’s design was initially conceived by three of his employees. The initial sketches and calculations of the proposed tower were made by office manager Emile Nouguier and engineer Maurice Koechlin in collaboration with architect Stephen Sauvestre. Sauvestre, in particular, was responsible for many of the design elements intended to turn what was essentially an oversized bridge pylon into an aesthetically-pleasing building. These design gestures, including the arches at the base of the tower and the bulbous finial at its summit, were intended to appeal not only to the public, but to Eiffel himself.[5]

The proposed design did not initially impress Eiffel, who nonetheless applied for patents in his, Nouguier’s, and Koechlin’s names. Later in 1884, he bought the two men out and began working directly with Sauvestre to refine the tower’s aesthetics. It was this iteration of the design that the two men submitted for consideration in 1886, and which was one of the three entries chosen among 107 submissions. In the end, the designers responsible for the other two winning designs were commissioned to build other major structures for the Exposition, while Eiffel and Sauvestre emerged as the final victors in the competition for the tower.[6]

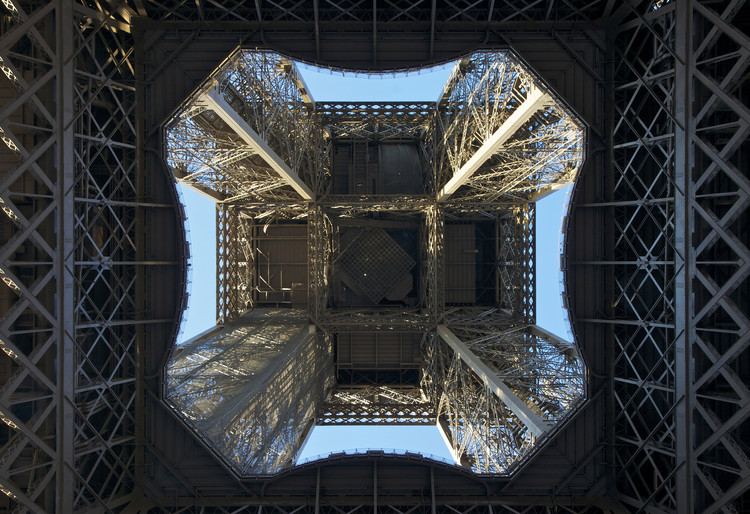

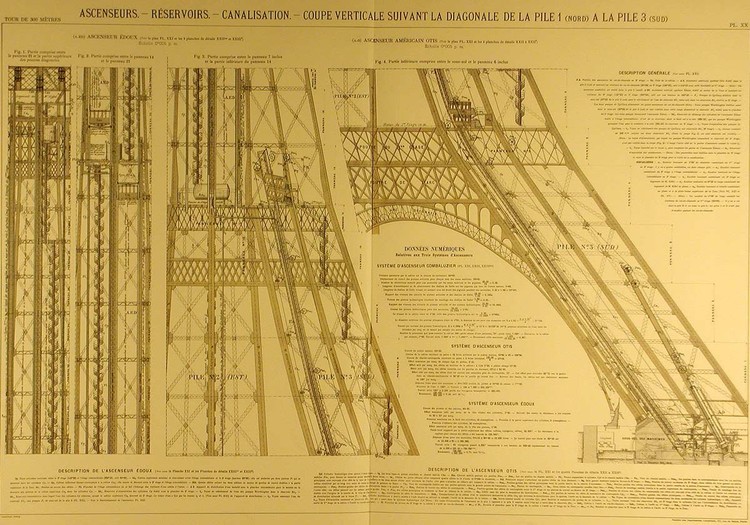

The Eiffel Tower comprises four iron lattice piers laid out in a square, rising from an initial slope of 54° and curving upward until they meet, at which point the tower rises as a single, subtly pyramidal form until the campanile at its summit. Its form was dictated primarily by concerns about wind at high altitudes, a matter which affected even the size and placement of rivet holes in the tower’s iron members.[7] Three floors are open to visitors, with the first and second levels suspended between the four piers and the third housed in the campanile, 324 meters (1063 feet) above the ground.[8] Before construction began, Eiffel calculated that the tower would weigh 6,500 metric tons and cost 3,155,000 francs; as built, the Eiffel Tower weighs 7,300 tons, and cost two and a half times as much as was expected.[9]

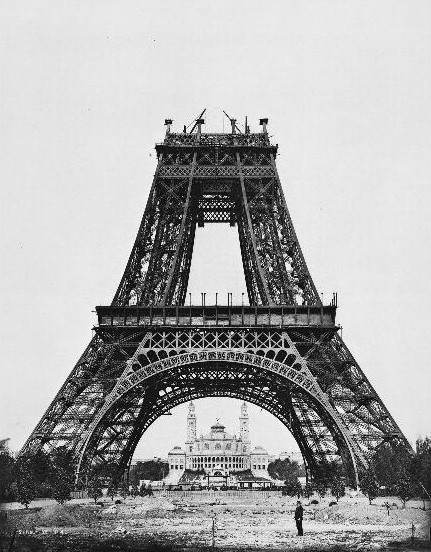

Despite its unprecedented height, the Eiffel Tower took a relatively small force of 300 workers only two years to build.[10] 18,000 pieces of ironwork were fabricated in Eiffel’s foundry in the suburb of Levallois-Perret, at which point they were transported to the Champ de Mars and lifted into place by steam cranes. Many of Sauvestre’s decorative flourishes were abandoned as the work proceeded, reducing both the construction cost and the weight of the tower. Surprisingly, there was only a single work-related fatality.[11, 12]

The growing tower provoked impassioned reactions in the Parisians who watched it rise beside the River Seine. Its wrought iron framework, seen as a symbol of the widening rift between architecture and engineering, was odious to much of the city’s artistic community. Some decried the tower as “monstrous and unnecessary,” while others compared it to a “black, gigantic factory chimney.” Its detractors included architect Charles Garnier, famed for the Opéra that bears his name, the playwright Alexandre Dumas, and writer Guy de Maupassant – the latter of whom frequently lunched at the tower in later years, as he claimed it was “the only place in Paris where I don’t have to see it.”[13, 14]

Opposition to the project proved fruitless, and Gustave Eiffel raised the French tricolor atop the completed tower in March of 1889, a full month ahead of schedule.[15] It was opened to the public two months later, drawing droves of visitors who wished to observe Paris as they never could have before. Those wishing to see an aerial view of the city ascended either by climbing one of the lengthy staircases hidden in the base pylons, or in one of a quartet of elevators designed on an articulated piston system that allowed them to follow the tower’s changing slope up to the first level. Here, visitors could take in the view from a covered arcade, as well as dine in one of four internationally-themed restaurants; the more daring could take two more sets of elevators to the second level, and subsequently to the campanile. At its opening, the system of elevators and staircases was designed to allow 5000 people to visit the Eiffel Tower each hour.[16]

.jpg?1480629521)

The Eiffel Tower soon proved to be a sensational international success. Nothing like it had ever been seen – it was twice the height of the Washington Monument, previously the tallest building in the world, and its novel method of construction only added to the effect.[17] In the 173 days the Exposition was open, over two million visitors from around the world paid to ascend its slender iron form. It made back its initial budget within a year, vindicating the financial contributions of both Eiffel and his investors. However, public interest waned quickly in the years following the Exposition; in 1890, visitorship fell to a fifth of what it had been the previous year. As the intended demolition date of 1909 loomed on the horizon, Gustave Eiffel vigorously defended the tower as uniquely valuable for the study of physics and meteorology.[18] In the debates that raged over the tower, however, it was ultimately not scientific utility that would see it preserved but its ability to be used as a radio (and later television) transmission tower.[19]

In the last century, the Eiffel Tower has come back from the brink of demolition to become one of the world’s most iconic monuments. It held the title of World’s Tallest Building for forty years, and by the time it lost that honor to New York City’s Chrysler Building, it had acquired a newer, greater significance for the people of France. The iconic nature of the Eiffel Tower has turned it into a symbol of both its nation and the city of Paris, with numerous replicas built in cities around the globe. Seven million people visit the tower every year, with much the same desire as their predecessors in 1889: to see the “City of Lights” from a stunning vista made possible by industrial innovation, nationalist fervor, and human scientific progress.[20, 21]

References

[1] Tissandier, Gaston. The Eiffel Tower a Description of the Monument, Its Construction, Its Machinery, Its Object, and Its Utility. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington St Dunstan's House Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C., 1889. p16.

[2] The Eiffel Tower: Marvels of Engineering. 2014: Marvels of Engineering.

[3] Hanser, David A. Architecture of France. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006. p63-64.

[4] Lemoine, Bertrand. Gustave Eiffel. Paris: F. Hazan, 1984. p126-130.

[5] Hanser, p65.

[6] Cowan, Henry J., and Trevor Howells. A Guide to the World's Greatest Buildings: Masterpieces of Architecture & Engineering. San Francisco, 2000: Fog City Press. p240-241.

[7] Tissandier, p18-31.

[8] "Key Figures: Visitors, Height, Lighting, Number of Steps, Paintwork..." La Tour Eiffel. Accessed October 11, 2016. [access].

[9] Hanser, p66.

[10] Cowan and Howells, p240.

[11] Hanser, p66.

[12] Ayers, Andrew. The Architecture of Paris: An Architectural Guide. Stuttgart: Edition Axel Menges, 2004. p139.

[13] Cowan and Howells, p241.

[14] Hanser, p66-67.

[15] Ayers, p139.

[16] Tissandier, p69-81.

[17] Tissandier, p16.

[18] Hanser, p66-67.

[19] Cowan and Howells, p241.

[20] "Key Figures: Visitors, Height, Lighting, Number of Steps, Paintwork..."

[21] "The Eiffel Tower in the World." La Tour Eiffel. Accessed October 11, 2016. [access].

-

Architects: Gustave Eiffel

- Area: 15625 m²

- Year: 1889

.jpg?1480629521)

.jpg?1480629521)